Google also releases an open-source version without stable releases or quality assurance under the name mozc. As it is open source, it can be used on Linux-based systems, whereas Google Japanese Input is limited to Windows, MacOS, and Chrome OS. It does not use Google's closed-source algorithms for generating dictionary data from online sources.[3]

Saturday, October 28, 2017

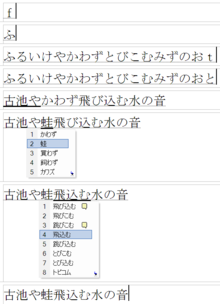

Mozc (Google Japanese Input)

Google Japanese Input (Google 日本語入力 Gūguru Nihongo Nyūryoku) is an input method published by Google for the entry of Japanese text on a computer. Since its dictionaries are generated automatically from the Internet, it is much easier to type personal names, Internet slang, neologisms and related terms.

Google also releases an open-source version without stable releases or quality assurance under the name mozc. As it is open source, it can be used on Linux-based systems, whereas Google Japanese Input is limited to Windows, MacOS, and Chrome OS. It does not use Google's closed-source algorithms for generating dictionary data from online sources.[3]

Google also releases an open-source version without stable releases or quality assurance under the name mozc. As it is open source, it can be used on Linux-based systems, whereas Google Japanese Input is limited to Windows, MacOS, and Chrome OS. It does not use Google's closed-source algorithms for generating dictionary data from online sources.[3]

Anthy

Anthy is a package for an input method editor backend for Unix-like systems for the Japanese language. It can convert Hiragana to Kanji as per the language rules. As a preconversion stage, Latin characters (Romaji) can be used to input Hiragana. Anthy is commonly used with an input method framework such as ibus, fcitx or SCIM.

As of January 2014, ibus-anthy is mature and stable, and can be used to author Japanese documents in LibreOffice version 4.1 by typing Romaji on a U.S. keyboard into a U.S. English localized LibreOffice installation. The Romaji is converted to Hiragana on-the-fly, and the Hiragana is likewise optionally converted to Kanji, with multiple Kanji equivalents presented for selection. The interface is well integrated into LibreOffice.

Anthy is free software released under the GNU GPL v2.

The input method is named after Anthy Himemiya, a character from the anime Revolutionary Girl Utena.

As of January 2014, ibus-anthy is mature and stable, and can be used to author Japanese documents in LibreOffice version 4.1 by typing Romaji on a U.S. keyboard into a U.S. English localized LibreOffice installation. The Romaji is converted to Hiragana on-the-fly, and the Hiragana is likewise optionally converted to Kanji, with multiple Kanji equivalents presented for selection. The interface is well integrated into LibreOffice.

Anthy is free software released under the GNU GPL v2.

The input method is named after Anthy Himemiya, a character from the anime Revolutionary Girl Utena.

References

- The Heke Project, under which Anthy is developed (in Japanese)

- WinAnthy, a Windows-Front-End for Anthy (in Japanese)

Japanese input methods

Japanese input methods are the methods used to input Japanese characters on a computer.

There are two main methods of inputting Japanese on computers. One is via a romanized version of Japanese called rōmaji (literally "Roman letters"), and the other is via keyboard keys corresponding to the Japanese kana. Some systems may also work via a graphical user interface, or GUI, where the characters are chosen by clicking on buttons or image maps.

Japanese keyboards (as shown on the second image) have both hiragana and Roman letters indicated. The JIS, or Japanese Industrial Standard, keyboard layout keeps the Roman letters in the English QWERTY layout, with numbers above them. Many of the non-alphanumeric

symbols are the same as on English-language keyboards, but some symbols

are located in other places. The hiragana symbols are also ordered in a

consistent way across different keyboards. For example, the Q, W, E, R, T, Y keys correspond to た, て, い, す, か, ん respectively (the English sounds for the previous hiragana symbols are: ta, te, i, su, ka, and n respectively) when the computer is used for direct hiragana input.

On most Japanese keyboards, one key switches between Roman characters and Japanese characters. Sometimes, each mode (Roman and Japanese) may even have its own key, in order to prevent ambiguity when the user is typing quickly.

There may also be a key to instruct the computer to convert the latest hiragana characters into kanji, although usually the space key serves the same purpose since Japanese writing doesn't use spaces.

Some keyboards have a mode key to switch between different forms of writing. This of course would only be the case on keyboards that contain more than one set of Japanese symbols. Hiragana, katakana, halfwidth katakana, halfwidth Roman letters, and fullwidth Roman letters are some of the options. A typical Japanese character is square while Roman characters are typically variable in width. Since all Japanese characters occupy the space of a square box, it is sometimes desirable to input Roman characters in the same square form in order to preserve the grid layout of the text. These Roman characters that have been fitted to a square character cell are called fullwidth, while the normal ones are called halfwidth. In some fonts these are fitted to half-squares, like some monospaced fonts, while in others they are not. Often, fonts are available in two variants, one with the halfwidth characters monospaced, and another one with proportional halfwidth characters. The name of the typeface with proportional halfwidth characters is often prefixed with "P" for "proportional".

Finally, a keyboard may have a special key to tell the OS that the last kana entered should not be converted to kanji. Sometimes this is just the Return/Enter key.

The kana-to-kanji conversion is done in the same way as when using any other type of keyboard. There are dedicated conversion keys on some designs, while on others the thumb shift keys double as such.

The primary system used to input Japanese on mobile phones is based

on the numerical keypad. Each number is associated with a particular

sequence of kana, such as ka, ki, ku, ke, ko for '2', and the button is pressed repeatedly to get the correct kana – each key corresponds to a column in the gojūon (5 row × 10 column grid of kana), while the number of presses determines the row.[1] Dakuten and handakuten

marks, punctuation, and other symbols can be added by other buttons in

the same way. Kana to kanji conversion is done via the arrow and other

keys.

If the hiragana is required, pressing the Enter key immediately after the characters are entered will end the conversion process and results in the hiragana as typed. If katakana is required, it is usually presented as an option along with the kanji choices. Alternatively, on some keyboards, pressing the muhenkan (無変換) (literally "no conversion") button switches between katakana and hiragana.

Sophisticated kana to kanji converters (known collectively as input method editors,

or IMEs), allow conversion of multiple kana words into kanji at once,

freeing the user from having to do a conversion at each stage. The user

can convert at any stage of input by pressing the space bar or henkan

button, and the converter attempts to guess the correct division of

words. Some IME programs display a brief definition of each word in

order to help the user choose the correct kanji.

Sometimes the kana to kanji converter may guess the correct kanji for all the words, but if it does not, the cursor (arrow) keys may be used to move backwards and forwards between candidate words. If the selected word boundaries are incorrect, the word boundaries can be moved using the control key (or shift key, e.g. on iBus-Anthy) plus the arrow keys.

There are two main methods of inputting Japanese on computers. One is via a romanized version of Japanese called rōmaji (literally "Roman letters"), and the other is via keyboard keys corresponding to the Japanese kana. Some systems may also work via a graphical user interface, or GUI, where the characters are chosen by clicking on buttons or image maps.

Contents

Japanese keyboards

Microsoft's gaming keyboard for the Japanese market

Apple MacBook Pro Japanese Keyboard

Input keys

See also: Language input keys

Since Japanese input requires switching between Roman and hiragana entry modes, and also conversion between hiragana and kanji

(as discussed below), there are usually several special keys on the

keyboard. This varies from computer to computer, and some OS vendors

have striven to provide a consistent user interface regardless of the type of keyboard being used. On non-Japanese keyboards, option- or control- key sequences can perform all of the tasks mentioned below.On most Japanese keyboards, one key switches between Roman characters and Japanese characters. Sometimes, each mode (Roman and Japanese) may even have its own key, in order to prevent ambiguity when the user is typing quickly.

There may also be a key to instruct the computer to convert the latest hiragana characters into kanji, although usually the space key serves the same purpose since Japanese writing doesn't use spaces.

Some keyboards have a mode key to switch between different forms of writing. This of course would only be the case on keyboards that contain more than one set of Japanese symbols. Hiragana, katakana, halfwidth katakana, halfwidth Roman letters, and fullwidth Roman letters are some of the options. A typical Japanese character is square while Roman characters are typically variable in width. Since all Japanese characters occupy the space of a square box, it is sometimes desirable to input Roman characters in the same square form in order to preserve the grid layout of the text. These Roman characters that have been fitted to a square character cell are called fullwidth, while the normal ones are called halfwidth. In some fonts these are fitted to half-squares, like some monospaced fonts, while in others they are not. Often, fonts are available in two variants, one with the halfwidth characters monospaced, and another one with proportional halfwidth characters. The name of the typeface with proportional halfwidth characters is often prefixed with "P" for "proportional".

Finally, a keyboard may have a special key to tell the OS that the last kana entered should not be converted to kanji. Sometimes this is just the Return/Enter key.

Thumb-shift keyboards

Main article: Thumb-shift keyboard

A thumb-shift keyboard

is an alternative design, popular among professional Japanese typists.

Like a standard Japanese keyboard, it has hiragana characters marked in

addition to Latin letters, but the layout is completely different. Most

letter keys have two kana characters associated with them, which allows

all the characters to fit in three rows, like in Western layouts. In the

place of the space bar key on a conventional keyboard, there are two

additional modifier keys, operated with thumbs - one of them is used to

enter the alternate character marked, and the other is used for voiced

sounds. The semi-voiced sounds are entered using either the conventional

shift key operated by the little finger, or take place of the voiced

sound for characters not having a voiced variant.The kana-to-kanji conversion is done in the same way as when using any other type of keyboard. There are dedicated conversion keys on some designs, while on others the thumb shift keys double as such.

Romaji input

As an alternative to direct input of kana, a number of Japanese input method editors allow Japanese text to be entered using romaji, which can then be converted to kana or kanji. This method does not require the use of a Japanese keyboard with kana markings.Mobile phones

See also: Japanese mobile phone culture

Keitai input

Japanese mobile phone keypad (Model Samsung 708SC)

Flick input

Flick input is a Japanese input method used on smartphones. The key layout is the same as the Keitai input, but rather than tapping the key repeatedly, the user can swipe the key in a certain direction to produce the desired vowel.[1] Smartphone Japanese IMEs such as Google Japanese Input, POBox and S-Shoin all support flick input.

Flick input

Godan layout

In addition to the industry standard QWERTY and 12 key layouts, Google Japanese Input offers a Godan keyboard layout, which is an alphabet layout optimized for romaji input. The letters fit in a five rows by three columns grid. The left column consists of the five vowels, while the right side consists of letters for the main voiceless consonants. Other characters, such as voiced consonants, handakuon, non-Japanese consonants, and numbers are typed by flick gesture. Unlike the 12 key input, repeating a key in Godan is not interpreted as a gesture to cycle through kana with different vowels, but rather it would be interpreted as a repeated romaji letter behaving the same as in the QWERTY layout mode.[2]| Layout | Desktop | Keitai | Smart phone | Cycling input | Flick input | Romaji input |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 key | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| QWERTY | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Godan | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

Other

Other consumer devices in Japan which allow for text entry via on-screen programming, such as digital video recorders and video game consoles, allow the user to toggle between the numerical keypad and a full keyboard (QWERTY, or ABC order) input system.Kana to kanji conversion

After the kana have been input, they are either left as they are, or converted into kanji (Chinese characters). The Japanese language has many homophones, and conversion of a kana spelling (representing the pronunciation) into a kanji (representing the standard written form of the word) is often a one-to-many process. The kana to kanji converter offers a list of candidate kanji writings for the input kana, and the user may use the space bar or arrow keys to scroll through the list of candidates until they reach the correct writing. On reaching the correct written form, pressing the Enter key, or sometimes the "henkan" key, ends the conversion process. This selection can also be controlled through the GUI with a mouse or other pointing device.If the hiragana is required, pressing the Enter key immediately after the characters are entered will end the conversion process and results in the hiragana as typed. If katakana is required, it is usually presented as an option along with the kanji choices. Alternatively, on some keyboards, pressing the muhenkan (無変換) (literally "no conversion") button switches between katakana and hiragana.

Operation of a typical IME

Sometimes the kana to kanji converter may guess the correct kanji for all the words, but if it does not, the cursor (arrow) keys may be used to move backwards and forwards between candidate words. If the selected word boundaries are incorrect, the word boundaries can be moved using the control key (or shift key, e.g. on iBus-Anthy) plus the arrow keys.

Learning systems

Modern systems learn the user's preferences for conversion and put the most recently selected candidates at the top of the conversion list, and also remember which words the user is likely to use when considering word boundaries.Predictive systems

The systems used on mobile phones go even further, and try to guess entire phrases or sentences. After a few kana have been entered, the phone automatically offers entire phrases or sentences as possible completion candidates, jumping beyond what has been input. This is usually based on words sent in previous messages.Japanese language and computers

In relation to the Japanese language and computers many adaptation issues arise, some unique to Japanese and others common to languages

which have a very large number of characters. The number of characters

needed in order to write English is very small, and thus it is possible

to use only one byte

to encode one English character. However, the number of characters in

Japanese is much more than 256, and hence Japanese cannot be encoded

using only one byte, and Japanese is thus encoded using two or more

bytes, in a so-called "double byte" or "multi-byte" encoding. Some

problems relate to transliteration and romanization, some to character encoding, and some to the input of Japanese text.

For example, most Japanese emails are in ISO-2022-JP ("JIS encoding") and web pages in Shift-JIS and yet mobile phones in Japan usually use some form of Extended Unix Code. If a program fails to determine the encoding scheme employed, it can cause mojibake (文字化け, "misconverted garbled/garbage characters", literally "transformed characters") and thus unreadable text on computers.

The first encoding to become widely used was JIS X 0201, which is a single-byte encoding that only covers standard 7-bit ASCII characters with half-width katakana extensions. This was widely used in systems that were neither powerful enough nor had the storage to handle kanji (including old embedded equipment such as cash registers). This means that only katakana, not kanji, was supported using this technique. Some embedded displays still have this limitation.

The development of kanji encodings was the beginning of the split. Shift JIS supports kanji and was developed to be completely backward compatible with JIS X 0201, and thus is in much embedded electronic equipment.

However, Shift JIS has the unfortunate property that it often breaks any parser (software that reads the coded text) that is not specifically designed to handle it. For example, a text search method can get false hits if it is not designed for Shift JIS. EUC, on the other hand, is handled much better by parsers that have been written for 7-bit ASCII (and thus EUC encodings are used on UNIX, where much of the file-handling code was historically only written for English encodings). But EUC is not backwards compatible with JIS X 0201, the first main Japanese encoding. Further complications arise because the original Internet e-mail standards only support 7-bit transfer protocols. Thus RFC 1468 ("ISO-2022-JP", often simply called JIS encoding) was developed for sending and receiving e-mails.

In character set standards such as JIS, not all required characters are included, so gaiji (外字 "external characters") are sometimes used to supplement the character set. Gaiji may come in the form of external font packs, where normal characters have been replaced with new characters, or the new characters have been added to unused character positions. However, gaiji are not practical in Internet environments since the font set must be transferred with text to use the gaiji. As a result, such characters are written with similar or simpler characters in place, or the text may need to be written using a larger character set (such as Unicode) that supports the required character.

Unicode was intended to solve all encoding problems over all languages. The UTF-8 encoding used to encode Unicode in web pages does not have the disadvantages that Shift-JIS has. Unicode is supported by international software, and it eliminates the need for gaiji. There are still controversies, however. For Japanese, the kanji characters have been unified with Chinese; that is, a character considered to be the same in both Japanese and Chinese is given a single number, even if the appearance is actually somewhat different, with the precise appearance left to the use of a locale-appropriate font. This process, called Han unification, has caused controversy. The previous encodings in Japan, Taiwan Area, Mainland China and Korea have only handled one language and Unicode should handle all. The handling of Kanji/Chinese have however been designed by a committee composed of representatives from all four countries/areas. Unicode is slowly growing because it is better supported by software from outside Japan, but still (as of 2011) most web pages in Japanese use Shift-JIS. The Japanese Wikipedia uses Unicode.

There are two main systems for the romanization of Japanese, known as Kunrei-shiki and Hepburn; in practice, "keyboard romaji" (also known as wāpuro rōmaji or "word processor romaji") generally allows a loose combination of both. IME implementations may even handle keys for letters unused in any romanization scheme, such as L, converting them to the most appropriate equivalent. With kana input, each key on the keyboard directly corresponds to one kana. The JIS keyboard system is the national standard, but there are alternatives, like the thumb-shift keyboard, commonly used among professional typists.

At present, handling of downward text is incomplete. For example, HTML has no support for tategaki and Japanese users must use HTML tables to simulate it. However, CSS level 3 includes a property "writing-mode" which can render tategaki when given the value "vertical-rl" (i.e. top to bottom, right to left). Word processors and DTP software have more complete support for it.

Contents

Character encodings

There are several standard methods to encode Japanese characters for use on a computer, including JIS, Shift-JIS, EUC, and Unicode. While mapping the set of kana is a simple matter, kanji has proven more difficult. Despite efforts, none of the encoding schemes have become the de facto standard, and multiple encoding standards are still in use today.For example, most Japanese emails are in ISO-2022-JP ("JIS encoding") and web pages in Shift-JIS and yet mobile phones in Japan usually use some form of Extended Unix Code. If a program fails to determine the encoding scheme employed, it can cause mojibake (文字化け, "misconverted garbled/garbage characters", literally "transformed characters") and thus unreadable text on computers.

The first encoding to become widely used was JIS X 0201, which is a single-byte encoding that only covers standard 7-bit ASCII characters with half-width katakana extensions. This was widely used in systems that were neither powerful enough nor had the storage to handle kanji (including old embedded equipment such as cash registers). This means that only katakana, not kanji, was supported using this technique. Some embedded displays still have this limitation.

The development of kanji encodings was the beginning of the split. Shift JIS supports kanji and was developed to be completely backward compatible with JIS X 0201, and thus is in much embedded electronic equipment.

However, Shift JIS has the unfortunate property that it often breaks any parser (software that reads the coded text) that is not specifically designed to handle it. For example, a text search method can get false hits if it is not designed for Shift JIS. EUC, on the other hand, is handled much better by parsers that have been written for 7-bit ASCII (and thus EUC encodings are used on UNIX, where much of the file-handling code was historically only written for English encodings). But EUC is not backwards compatible with JIS X 0201, the first main Japanese encoding. Further complications arise because the original Internet e-mail standards only support 7-bit transfer protocols. Thus RFC 1468 ("ISO-2022-JP", often simply called JIS encoding) was developed for sending and receiving e-mails.

In character set standards such as JIS, not all required characters are included, so gaiji (外字 "external characters") are sometimes used to supplement the character set. Gaiji may come in the form of external font packs, where normal characters have been replaced with new characters, or the new characters have been added to unused character positions. However, gaiji are not practical in Internet environments since the font set must be transferred with text to use the gaiji. As a result, such characters are written with similar or simpler characters in place, or the text may need to be written using a larger character set (such as Unicode) that supports the required character.

Unicode was intended to solve all encoding problems over all languages. The UTF-8 encoding used to encode Unicode in web pages does not have the disadvantages that Shift-JIS has. Unicode is supported by international software, and it eliminates the need for gaiji. There are still controversies, however. For Japanese, the kanji characters have been unified with Chinese; that is, a character considered to be the same in both Japanese and Chinese is given a single number, even if the appearance is actually somewhat different, with the precise appearance left to the use of a locale-appropriate font. This process, called Han unification, has caused controversy. The previous encodings in Japan, Taiwan Area, Mainland China and Korea have only handled one language and Unicode should handle all. The handling of Kanji/Chinese have however been designed by a committee composed of representatives from all four countries/areas. Unicode is slowly growing because it is better supported by software from outside Japan, but still (as of 2011) most web pages in Japanese use Shift-JIS. The Japanese Wikipedia uses Unicode.

Text input

Main article: Japanese input methods

Written Japanese uses several different scripts: kanji (Chinese characters), 2 sets of kana

(phonetic syllabaries) and roman letters. While kana and roman letters

can be typed directly into a computer, entering kanji is a more

complicated process as there are far more kanji than there are keys on

most keyboards. To input kanji on modern computers, the reading of kanji

is usually entered first, then an input method editor

(IME), also sometimes known as a front-end processor, shows a list of

candidate kanji that are a phonetic match, and allows the user to choose

the correct kanji. More-advanced IMEs work not by word but by phrase,

thus increasing the likelihood of getting the desired characters as the

first option presented. Kanji readings inputs can be either via romanization (rōmaji nyūryoku, ローマ字入力) or direct kana input (kana nyūryoku, かな入力).

Romaji input is more common on PCs and other full-size keyboards

(although direct input is also widely supported), whereas direct kana

input is typically used on mobile phones and similar devices – each of

the 10 digits (1–9,0) corresponds to one of the 10 columns in the gojūon table of kana, and multiple presses select the row.There are two main systems for the romanization of Japanese, known as Kunrei-shiki and Hepburn; in practice, "keyboard romaji" (also known as wāpuro rōmaji or "word processor romaji") generally allows a loose combination of both. IME implementations may even handle keys for letters unused in any romanization scheme, such as L, converting them to the most appropriate equivalent. With kana input, each key on the keyboard directly corresponds to one kana. The JIS keyboard system is the national standard, but there are alternatives, like the thumb-shift keyboard, commonly used among professional typists.

Direction of text

Japanese can be written in two directions. Yokogaki style writes left-to-right, top-to-bottom, as with English. Tategaki style writes first top-to-bottom, and then moves right-to-left.At present, handling of downward text is incomplete. For example, HTML has no support for tategaki and Japanese users must use HTML tables to simulate it. However, CSS level 3 includes a property "writing-mode" which can render tategaki when given the value "vertical-rl" (i.e. top to bottom, right to left). Word processors and DTP software have more complete support for it.

VIQR (Vietnamese Quoted-Readable)

Vietnamese Quoted-Readable (usually abbreviated VIQR), also known as Vietnet, is a convention for writing Vietnamese using ASCII characters. Because the Vietnamese alphabet contains a complex system of diacritical marks, VIQR requires the user to type in a base letter, followed by one or two characters that represent the diacritical marks.

VIQR uses

Unlike the VISCII and VPS code pages, VIQR is rarely used as a character encoding. While VIQR is registered with the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority as a MIME charset, MIME-compliant software is not required to support it.[4] Nevertheless, the Mozilla Vietnamese Enabling Project once produced builds of the open source version of Netscape Communicator, as well as its successor, the Mozilla Application Suite, that were capable of decoding VIQR-encoded webpages, e-mails, and newsgroup messages. In these unofficial builds, a "VIQR" option appears in the Edit | Character Set menu, alongside the VISCII, TCVN 5712, VPS, and Windows-1258 options that remained available for several years in Mozilla Firefox and Thunderbird.[5][6]

In 1992, the Vietnamese Standardization Group (Viet-Std, Nhóm Nghiên Cứu Tiêu Chuẩn Tiếng Việt) from the TriChlor Software Group in California formalized the VIQR convention. It was described the next year in RFC 1456.

Contents

Syntax

VIQR uses the following convention:[1]| Diacritical mark | Typed character | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| trăng (breve) | ( |

a( → ă |

| mũ (circumflex) | ^ |

a^ → â |

| móc (horn) | +[2] |

o+ → ơ |

| huyền (grave) | ` |

a` → à |

| sắc (acute) | '[3] |

a' → á |

| hỏi (hook) | ? |

a? → ả |

| ngã (tilde) | ~ |

a~ → ã |

| nặng (dot below) | . |

a. → ạ |

DD or Dd for the Vietnamese letter Đ, and dd for the Vietnamese letter đ. To type certain punctuation marks (namely, the period, question mark, apostrophe, forward slash, opening parenthesis, or tilde) directly after most Vietnamese words, a backslash (\) must be typed directly before the punctuation mark, so that it will not be interpreted as a diacritical mark. For example:- O^ng te^n gi`\? To^i te^n la` Tra^`n Va(n Hie^'u\.

- Ông tên gì? Tôi tên là Trần Văn Hiếu.

- What is your name [Sir]? My name is Hiếu Văn Trần.

Software support

VIQR is primarily used as a Vietnamese input method in software that supports Unicode. Similar input methods include Telex and VNI. Input method editors such as VPSKeys convert VIQR sequences to Unicode precomposed characters as one types, typically allowing modifier keys to be input after all the base letters of each word. However, in the absence of input method software or Unicode support, VIQR can still be input using a standard keyboard and read as plain ASCII text without suffering from mojibake.Unlike the VISCII and VPS code pages, VIQR is rarely used as a character encoding. While VIQR is registered with the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority as a MIME charset, MIME-compliant software is not required to support it.[4] Nevertheless, the Mozilla Vietnamese Enabling Project once produced builds of the open source version of Netscape Communicator, as well as its successor, the Mozilla Application Suite, that were capable of decoding VIQR-encoded webpages, e-mails, and newsgroup messages. In these unofficial builds, a "VIQR" option appears in the Edit | Character Set menu, alongside the VISCII, TCVN 5712, VPS, and Windows-1258 options that remained available for several years in Mozilla Firefox and Thunderbird.[5][6]

History

By the early 1990s, an ad-hoc system of mnemonics known as Vietnet was in use on the Viet-Net mailing list and soc.culture.vietnamese Usenet group.[7][8]In 1992, the Vietnamese Standardization Group (Viet-Std, Nhóm Nghiên Cứu Tiêu Chuẩn Tiếng Việt) from the TriChlor Software Group in California formalized the VIQR convention. It was described the next year in RFC 1456.

VNI

VNI Software Company is the Westminster, California–based, family-owned developer of various education, entertainment, office, and utility software packages.

In the 1990s, Microsoft recognized the potential of VNI's products and incorporated VNI Input Method into Windows 95 Vietnamese Edition and MSDN, in use worldwide.

Upon Microsoft's unauthorized use of these technologies, VNI took Microsoft to court over the matter. Microsoft settled the case out of court, withdrew the input method from their entire product line, and developed their own input method. It has, although virtually unknown, appeared in every Windows release since Windows 98.

With VNI Tan Ky mode on, the user can type in diacritical marks

anywhere within a word, and the marks will appear at their proper

locations. For example, the word trường, which means "school", can be typed in the following ways:

With VNI Tan Ky mode on, the user can type in diacritical marks

anywhere within a word, and the marks will appear at their proper

locations. For example, the word trường, which means "school", can be typed in the following ways:

This solution is more portable between different versions of Windows and between different platforms. However, due to the presence of multiple characters in a file to represent one written character increases the file size. The increased file size can usually be accounted for by compressing the data into a file format such as ZIP.

VNI was the only well-known company to fully recognize the potential of VIQR.[citation needed] VIQR's main issue, however, was the difficulty of reading VIQR text, especially for inexperienced computer users. VNI created and released a free font called VNI-Internet Mail. VNI-Internet Mail utilized the VIQR encoding and VNI's two-character technique to give VIQR text a more natural appearance.

Contents

History

VNI was founded in 1987 by Hồ Thành Việt to develop software that eases Vietnamese language use on computers. Among their products were the VNI Encoding and VNI Input Method.VNI vs. Microsoft

|

This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (April 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

Upon Microsoft's unauthorized use of these technologies, VNI took Microsoft to court over the matter. Microsoft settled the case out of court, withdrew the input method from their entire product line, and developed their own input method. It has, although virtually unknown, appeared in every Windows release since Windows 98.

Unicode

Despite the growing popularity of Unicode in computing, the VNI Encoding (see below) is still in wide use by Vietnamese speakers both in Vietnam and abroad. All professional printing facilities in the Little Saigon neighborhood of Orange County, California continue to use the VNI Encoding when processing Vietnamese text. For this reason, print jobs submitted using the VNI Character Set are compatible with local printers.VNI products

VNI invented, popularized, and commercialized an input method and an encoding, the VNI Character Set, to assist computer users entering Vietnamese on their computers. The user can type using only ASCII characters found on standard computer keyboard layouts. Because the Vietnamese alphabet uses a complex system of diacritical marks, the keyboard needs 133 alphanumeric keys and a Shift key to cover all possible characters.VNI Input Method

Originally, VNI's input method utilized function keys (F1, F2, ...) to enter the tone marks, which later turned out to be problematic, as the operating system used those keys for other purposes. VNI then turned to the numerical keys along the top of the keyboard (as opposed to the numpad) for entering tone marks. This arrangement survives today, but users also have the option of customizing the keys used for tone marks.

Bảng dấu VNI: a toolbar allowing one-click access to Vietnamese diacritical marks

- 72truong → trường

- truo72ng → trường

- tr72uong → trường

- t72ruong → trường

- truo7ng2 → trường

- tru7o72ng → trường

VNI Tan Ky

With the release of VNI Tan Ky 4 in the 1990s, VNI freed users from having to remember where to correctly insert tone marks within a word, because, as long as the user enters all the required characters and tone marks, the software will group them correctly. This feature is especially useful for newcomers to the language.VNI Auto Accent

VNI Auto Accent is the company's most recent software release (2006), with the purpose of alleviating repetitive strain injury (RSI) caused by prolonged use of computer keyboards. Auto Accent helps reduce the number of keystrokes needed to type each word by automatically adding diacritical marks for the user. The user must still enter every base letter in the word.VNI Encoding

The VNI Encoding uses two characters to represent one Vietnamese vowel character, therefore removing the need for control characters to represent one Vietnamese character, a problematic system found in TCVN, or using two different fonts such as in VPSKeys, one containing lowercase characters and the other uppercase characters.This solution is more portable between different versions of Windows and between different platforms. However, due to the presence of multiple characters in a file to represent one written character increases the file size. The increased file size can usually be accounted for by compressing the data into a file format such as ZIP.

VIQR and VNI-Internet Mail

The use of Vietnamese Quoted-Readable (VIQR), a convention for writing in Vietnamese using ASCII characters, began during the Vietnam War, when typewriters were the main tool for word processing. Because the U.S. military required a way to represent Vietnamese scripts accurately on official documents, VIQR was invented for the military. Due to its longstanding use, VIQR was a natural choice for computer word processing, prior to the appearance of VNI, VPSKeys, VISCII, and Unicode. It is still widely used for information exchange on computers, but is not desirable for design and layout, due to its cryptic appearance.VNI was the only well-known company to fully recognize the potential of VIQR.[citation needed] VIQR's main issue, however, was the difficulty of reading VIQR text, especially for inexperienced computer users. VNI created and released a free font called VNI-Internet Mail. VNI-Internet Mail utilized the VIQR encoding and VNI's two-character technique to give VIQR text a more natural appearance.

Telex (input method)

Telex, also known in Vietnamese as Quốc ngữ điện tín (lit. "national language telex", is a convention for encoding Vietnamese text in plain ASCII characters. Originally used for transmitting Vietnamese text over telex systems, it is now a popular input method for computers.

In later decades, common computer systems came with largely the same limitations as the telex infrastructure, namely inadequate support for the large number of characters in Vietnamese. Mnemonics like Telex and Vietnamese Quoted-Readable (VIQR) were adapted for these systems. As a variable-width character encoding, Telex represents a single Vietnamese character as one, two, or three ASCII characters. By contrast, a byte-oriented code page like VISCII takes up only one byte per Vietnamese character but requires specialized software or hardware for input.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Telex was adopted as a way to type Vietnamese on standard English keyboards. Specialized software converted Telex keystrokes to either precomposed or decomposed Unicode text as the user typed. VietStar was the first such software package to support this entry mode. The Bked editor by Quách Tuấn Ngọc extended Telex with commands such as

In the 2000s, Unicode largely supplanted language-specific encodings on modern computer systems and the Internet, limiting Telex's use in text storage and transmission. However, it remains the default input method for many input method editors, with VIQR and VNI offered as alternatives. It also continues to supplement international Morse Code in Vietnamese telegraph transmissions.[2]

To write the pair of keys as two distinct characters, the second character has to be repeated. For example, the Vietnamese word cải xoong must be entered as

If more than one tone marking key is pressed, the last one will be used. For example, typing

--------------------

Contents

History

The Telex input method is based on a set of rules for transmitting accented Vietnamese text over telex (máy điện tín) first used in Vietnam during the 1920s and 1930s. Telex services at the time ran over infrastructure that was designed overseas to handle only a basic Latin alphabet, so a message reading "vỡ đê" ("the dam broke") could easily be misinterpreted as "vợ đẻ" ("the wife is giving birth"). Nguyễn Văn Vĩnh, a prominent journalist and translator, is credited with devising the original set of rules for telex systems.[1]In later decades, common computer systems came with largely the same limitations as the telex infrastructure, namely inadequate support for the large number of characters in Vietnamese. Mnemonics like Telex and Vietnamese Quoted-Readable (VIQR) were adapted for these systems. As a variable-width character encoding, Telex represents a single Vietnamese character as one, two, or three ASCII characters. By contrast, a byte-oriented code page like VISCII takes up only one byte per Vietnamese character but requires specialized software or hardware for input.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Telex was adopted as a way to type Vietnamese on standard English keyboards. Specialized software converted Telex keystrokes to either precomposed or decomposed Unicode text as the user typed. VietStar was the first such software package to support this entry mode. The Bked editor by Quách Tuấn Ngọc extended Telex with commands such as

z, [ for "ư", and ] for "ơ".[citation needed] It was further popularized with the input method editors VietKey, Vietres, and VPSKeys. In 1993, the use of Telex as an input method was standardized in Vietnam as part of TCVN 5712.In the 2000s, Unicode largely supplanted language-specific encodings on modern computer systems and the Internet, limiting Telex's use in text storage and transmission. However, it remains the default input method for many input method editors, with VIQR and VNI offered as alternatives. It also continues to supplement international Morse Code in Vietnamese telegraph transmissions.[2]

Rules

Because the Vietnamese alphabet uses a complex system of diacritical marks, Telex requires the user to type in a base letter, followed by one or two characters that represent the diacritical marks:| Character | Keys pressed | Sample input | Sample output |

|---|---|---|---|

| ă | aw | trawng | trăng |

| â | aa | caan | cân |

| đ | dd | ddaau | đâu |

| ê | ee | ddeem | đêm |

| ô | oo | nhoo | nhô |

| ơ | ow | mow | mơ |

| ư | uw | tuw | tư |

cari xooong rather than cari xoong (*cải xông).| Tone | Keys added to syllable | Sample input | Sample output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ngang (level) | z or nothing | ngang | ngang |

| Huyền (falling) | f | huyeenf | huyền |

| Sắc (rising) | s | sawcs | sắc |

| Hỏi (dipping-rising) | r | hoir | hỏi |

| Ngã (rising glottalized) | x | ngax | ngã |

| Nặng (falling glottalized) | j | nawngj | nặng |

asz will return "a". (Thus z

can also be used to delete diacritics when using an input method

editor.) To write a tone marking key as a normal character, one has to

press it twice: her becomes hẻ, while herr becomes her.--------------------

Linux input method

I am trying to keep this article concise for you to make you have

an outline of current condition of Linux (and maybe other platforms like

BSDs) input methods. It’s coverage is mostly CJK languages, but I think

other languages that use input method would be sure to find there

examples in this article. We will start with the most popular ones, and

there will be some hints about other ones at last.

Before we start our tour, there are two concepts to know, input method framework and input method engine:

An input method framework is designed to serve as a daemon and

handle user input events, output the result to target applications or

layers.

An input method engine is a program to analyze inputed characters and

calculate a list of probably results, then send the results to their

hosted input method framework to complete the reaction with users and

applications.

1. SCIM (Smart Common Input Method)

Most Linux input method users may have the experience of using SCIM, which is created by Chinese developer Su Zhe for promoting his Intelligent Pinyin input method and providing a better input method framework.

Some friends of mine are still keep using SCIM even though it is not being maintained, nor SKIM, its sister project on KDE. SCIM was the default choice of distros for years. People developed lots of input method engines for it, for example scim-pinyin, which has been mentioned above as Intelligent Pinyin input method. Users may be also familiar with scim-python, scim-xingma-*, scim-googlepinyin and the still-maintained scim-sunpinyin.

On a distro maker’s point of view, the glorious age of SCIM has just finished.

2. IBus (Intelligent Input Bus)

IBus is the de facto standard of input method framework on nowadays Linux distros, whose author is a Chinese developer, Huang Peng, who has been mentioned as the author of scim-python and scim-xingma-*. IBus is aiming at a “next generation input framework” comparing to SCIM. I think this goal has been achieved – new comers may only know IBus from the very beginning of his adventure on Linux.

IBus is written in C++, and is designed to be highly modularized: core input bus, gtk/qt interfaces, python binding, table engine, table modules and other input method engines. It uses Gtk immodule, thus is the best choice for GTK+ applications. What’s more, Flash Player support Gtk immodule only and IBus has no problem to work with it. The author of IBus is really helpful with other input engine developers, so there are many input method engines available on IBus framework.

But IBus has obvious limitations from its design:

Firstly, it uses Gtk immodule only, which benefit GTK+ platform applications, but do poorly with QT.

Secondly, it depends on gconf, which is unacceptable for some users and distro makers (most of them are anti-gnome holic).

Thirdly, the most used input engine, ibus-pinyin is written in

Python that caused serious performance limitation. And this engine has

had some severe bugs like memory leak and dead loop (100%). Even though

the condition is largely improved, users are still complaining about

them.

Fourthly, the alternative Pinyin engine ibus-sunpinyin is not well maintained, and really lacks of testing. There are some obvious bug leaving their without people interested to fix.

Note: ibus-pinyin has been rewritten in mainly C++

with many improvements, and such changes will land on major in very near

future (maybe some of them have already published it, I didn’t do a

detailed research here).

3. Fcitx (Free Chinese Input Toy for X)

Fcitx is an old and new input method. It bears at the same time as SCIM, and now gets a new life with the brand new 4.x series. As name suggests, it is first designed to be a Chinese specific input method by Yuking. During 3.x series, the aim of being a feature rich Chinese input method gave it quite a few of fans, but also kept it from being a default choice of major distros. Fcitx uses XIM, which works well for most platforms (like GTK+ and QT), but has some small problems.

However, starting from 4.x series, Fcitx has been given a new goal with a new maintainer – a college student at Peking University, Weng Xuetian. Now he has published 4.0.1, the second version of 4.x series, with features like customizable skins, tables which has been wanted for a long time. It has been heavily modularized: all tables are separated, developer-friendly input method engine interface, graphic user configuration tool. Also, 4.x series does not use GBK encoded Chinese configuration files anymore, and UTF-8 encoded English configuration files are used. I would like to highlight its perfect user experience of fcitx-sunpinyin, it is worthwhile for every Pinyin users to give a try.

There are still issues on its way of (probably) being the default of distros:

Though the author has promised Gtk immodule support in 4.1.0 release, the feature is still not available now.

The internal Pinyin input method is old, and still not being

separate out from the framework core because of too close integration

before. The work will be done in 4.1.0 as well.

Fcitx is still lacking of people who are interested in developing

input method engines, even if the interface is more friendly to

developers. There is an example, fcitx-sunpinyin (written in C++) has

only ~300 lines to make everything work perfectly with libsunpinyin.

Properly speaking, Fcitx is still not a input method framework

because of the reasons listed above, but it will be, also as said above.

Above are the most famous input methods, here is a list of other things in Linux input methods with short descriptions.

1. ucimf (Unicode Console Input Method Framework)

ucimf is an input method framework for Linux unicode framebuffer console, which is mainly with fbterm and jfberm. It is developed by Chinese developer, Mat. He maintains a series of input method engines ported from BSD licensed Mac OSX input method OpenVanilla.

There are other solutions under framebuffer console, for example ibus-fbterm (development has stopped), but I still recommend to use ucimf because it full featured and well maintained.

2. SunPinyin

One thing to clarify, Sunpinyin isn’t a frame work, but it is important so I would like to mention it here. We have mentioned scim-sunpinyin, ibus-sunpinyin and the recommended fcitx-sunpinyin. In fact there is also a standalone xsunpinyin alive. SunPinyin is a statistical language model based Chinese input method, which was firstly developed by Sun Beijing Globalization team, and opened source to community with Opensolaris project, with LGPLv2 and CDDL dual-licenses.

SunPinyin would be heavily used from now on, it is the best Pinyin engine on Linux and some other platforms.

3. SCIM2

SCIM2 was trying to be a next generation SCIM, but abandoned because of the emerging star during that period – IBus.

4. ImBus

ImBus is created by the author of SCIM, and he would like to make it a general input method framework including all known best techniques with minimal dependencies. But the project halted with the same reason like SCIM2, no code in its svn repository.

5. Fitx (Fun Input Toy for Linux)

Fitx was a flash in the pan on Linux, the project stopped soon after its emerging. Fitx is a ported version of FIT input method on Mac OSX, but implemented using SCIM framework.

6. gcin

gcin is a input method developed by traditional Chinese community, targeted to traditional Chinese users.

7. uim

uim is a input method framework made by Japanese developers. It is a little different because uim isn’t an input method server (XIM is a server), it’s just a library. Because the designer believe many people don’t need a full featured platform but only something enough to work.

For information about input method types, there is a good website: http://seba.studentenweb.org/thesis/im.php

Update:

2011-01-15 21:30

Thanks to Zhengpeng Hou, I’ve added some description about uim, and a notice about whether fcitx should be considered as a framework now.

2011-01-28 00:15

Thanks to Shawn P Huang, ibus-pinyin has been rewritten in mainly C++ with many improvements.

Before we start our tour, there are two concepts to know, input method framework and input method engine:

Most Linux input method users may have the experience of using SCIM, which is created by Chinese developer Su Zhe for promoting his Intelligent Pinyin input method and providing a better input method framework.

Some friends of mine are still keep using SCIM even though it is not being maintained, nor SKIM, its sister project on KDE. SCIM was the default choice of distros for years. People developed lots of input method engines for it, for example scim-pinyin, which has been mentioned above as Intelligent Pinyin input method. Users may be also familiar with scim-python, scim-xingma-*, scim-googlepinyin and the still-maintained scim-sunpinyin.

On a distro maker’s point of view, the glorious age of SCIM has just finished.

2. IBus (Intelligent Input Bus)

IBus is the de facto standard of input method framework on nowadays Linux distros, whose author is a Chinese developer, Huang Peng, who has been mentioned as the author of scim-python and scim-xingma-*. IBus is aiming at a “next generation input framework” comparing to SCIM. I think this goal has been achieved – new comers may only know IBus from the very beginning of his adventure on Linux.

IBus is written in C++, and is designed to be highly modularized: core input bus, gtk/qt interfaces, python binding, table engine, table modules and other input method engines. It uses Gtk immodule, thus is the best choice for GTK+ applications. What’s more, Flash Player support Gtk immodule only and IBus has no problem to work with it. The author of IBus is really helpful with other input engine developers, so there are many input method engines available on IBus framework.

But IBus has obvious limitations from its design:

3. Fcitx (Free Chinese Input Toy for X)

Fcitx is an old and new input method. It bears at the same time as SCIM, and now gets a new life with the brand new 4.x series. As name suggests, it is first designed to be a Chinese specific input method by Yuking. During 3.x series, the aim of being a feature rich Chinese input method gave it quite a few of fans, but also kept it from being a default choice of major distros. Fcitx uses XIM, which works well for most platforms (like GTK+ and QT), but has some small problems.

However, starting from 4.x series, Fcitx has been given a new goal with a new maintainer – a college student at Peking University, Weng Xuetian. Now he has published 4.0.1, the second version of 4.x series, with features like customizable skins, tables which has been wanted for a long time. It has been heavily modularized: all tables are separated, developer-friendly input method engine interface, graphic user configuration tool. Also, 4.x series does not use GBK encoded Chinese configuration files anymore, and UTF-8 encoded English configuration files are used. I would like to highlight its perfect user experience of fcitx-sunpinyin, it is worthwhile for every Pinyin users to give a try.

There are still issues on its way of (probably) being the default of distros:

Above are the most famous input methods, here is a list of other things in Linux input methods with short descriptions.

1. ucimf (Unicode Console Input Method Framework)

ucimf is an input method framework for Linux unicode framebuffer console, which is mainly with fbterm and jfberm. It is developed by Chinese developer, Mat. He maintains a series of input method engines ported from BSD licensed Mac OSX input method OpenVanilla.

There are other solutions under framebuffer console, for example ibus-fbterm (development has stopped), but I still recommend to use ucimf because it full featured and well maintained.

2. SunPinyin

One thing to clarify, Sunpinyin isn’t a frame work, but it is important so I would like to mention it here. We have mentioned scim-sunpinyin, ibus-sunpinyin and the recommended fcitx-sunpinyin. In fact there is also a standalone xsunpinyin alive. SunPinyin is a statistical language model based Chinese input method, which was firstly developed by Sun Beijing Globalization team, and opened source to community with Opensolaris project, with LGPLv2 and CDDL dual-licenses.

SunPinyin would be heavily used from now on, it is the best Pinyin engine on Linux and some other platforms.

3. SCIM2

SCIM2 was trying to be a next generation SCIM, but abandoned because of the emerging star during that period – IBus.

4. ImBus

ImBus is created by the author of SCIM, and he would like to make it a general input method framework including all known best techniques with minimal dependencies. But the project halted with the same reason like SCIM2, no code in its svn repository.

5. Fitx (Fun Input Toy for Linux)

Fitx was a flash in the pan on Linux, the project stopped soon after its emerging. Fitx is a ported version of FIT input method on Mac OSX, but implemented using SCIM framework.

6. gcin

gcin is a input method developed by traditional Chinese community, targeted to traditional Chinese users.

7. uim

uim is a input method framework made by Japanese developers. It is a little different because uim isn’t an input method server (XIM is a server), it’s just a library. Because the designer believe many people don’t need a full featured platform but only something enough to work.

For information about input method types, there is a good website: http://seba.studentenweb.org/thesis/im.php

Update:

2011-01-15 21:30

Thanks to Zhengpeng Hou, I’ve added some description about uim, and a notice about whether fcitx should be considered as a framework now.

2011-01-28 00:15

Thanks to Shawn P Huang, ibus-pinyin has been rewritten in mainly C++ with many improvements.

Friday, October 27, 2017

ÁP DỤNG: Tiếng việt trên Centos7

Buớc 1: cài ibus

yum install ibus

Buớc 2: cài ibus-m17n

yum install ibus-m17n

Bước 3: khởi động lại ibus

$ibus restart

Buớc 4: cấu hình gõ telex

All setting >> region and languages >> Input Sources >> Thêm vietnamese telex(m17n)

yum install ibus

Buớc 2: cài ibus-m17n

yum install ibus-m17n

Bước 3: khởi động lại ibus

$ibus restart

Buớc 4: cấu hình gõ telex

All setting >> region and languages >> Input Sources >> Thêm vietnamese telex(m17n)

Quora: How do Vietnamese people type Vietnamese letters?

There is indeed a Vietnamese keyboard layout that is included in all modern operating systems since

Windows 2000 (I don't know the exact time when it was included in other

OSes though). It's no different from US QWERTY layout except:

- Vietnamese-specific keys added in number/symbol key positions

- The keys' function swapped between typing characters and numbers/symbols.

There are also useless characters like cedilla Ç and OE ligature Œ that most Vietnamese people won’t have a clue what those are for.

So that means you can type Vietnamese without any 3ʳᵈ party software, although a bit uncomfortable.

However most people don't know this or consider this layout stupid because you cannot write the numbers and normal symbols like !@#$%^&... directly but you must type them with the AltGr modifier.

There is no keyboard produced based on this layout either, so nobody

uses this. Instead they use normal US QWERTY keyboards and VNI and Telex input method with some input method software (most commonly Unikey which replaced Vietkey) like others have said.

There are some other alternatives like WinVNKey and GoTiengViet

by Trần Kỳ Nam. Earlier, people would used Vietkey in Windows and

Vietres in DOS. In other operating systems there are other software

packages such as xunikey and iBus in Linux.

VNI

is more common in the South because most (if not all) teachers in the

South teach it to their students. Telex is more prevalent in the North

but some Southerners, after learning VNI in schools, try Telex

themselves and choose to switch to it because it makes typing faster,

especially when typing with ten fingers.

In

fact I've seen several Mitsumi keyboards labelled "Vietnamese keyboard

layout" on the box but they were not following this layout.

In

prior versions of Windows Phone, Microsoft also used this layout and

received a lot of criticism since it took so much valuable screen space

and was hard to type with since nobody was accustomed to it. Therefore

they had to create two more keyboard layouts using the common VNI and

Telex typing methods.

A new input method using VNI and Telex for Windows codenamed BlackCi (BLACK Ci)

supported and distributed by Microsoft is also being released in

various technology forums for public experiment. It was intended to be

the official Vietnamese input method to be included in windows 8 but for

some reason they aren't finished yet.

In older times Vietnamese typewriters were actually produced using two different keyboard layouts. One of them is like this:

The other layout is very different than the QWERTY. I tried hard but cannot find it.

I

was fortunate to have the luck of learning how to use typewriters and I

wonder why one of those layouts isn't the official layout for

Vietnamese keyboards. It would make typing Vietnamese faster. I don't

know who invented the current Vietnamese keyboard layout used in

computer OSes mentioned in the beginning of this answer but it's really

silly and ridiculous while VNI and Telex make some characters three

strokes to type and that's undesirable.

EDIT:

I think I have found the other Vietnamese keyboard layout for typewriters:

I think I have found the other Vietnamese keyboard layout for typewriters:

--------------------

On Google Translate

you can set the source language to Vietnamese, which will then show you

a button [ ê ] to select an input method. Select TELEX (which is

probably the most commonly used).

Once

you have selected it, you can type something in Vietnamese using the

TELEX rules (the mapping of keys to diacritics has been mentioned in

other answers).

An example: type

nuowcs Vieetj Nam, ddoocj laapj - tuwj do - hanhj phucs

to get

(meaning “country of Vietnam, independence - freedom - happiness”, the official motto of VN)

Văn bản trên máy tính

Tôi có 2 câu hỏi:

Câuhỏi 1:

Khi gõ 1 văn bản trên máy tínhsửdụngbàn phím QWERTY thì thuờng sẽ chỉ gõ đuợc các ký tự tiếng anh (26 chữ cái)

Các ký tự CJK (Chinese Japanese Korean) và ký tự tiếng việt sẽ không gõ đuợc

Vậy làm cách nào để gõ các ký tự mà bàn phím không có?

Trả lời: phải sử dụng các Input Method

Câu hỏi 2:

Thông thuờng máy tính chỉ hiển thị các văn bản tiếng anh (26 chữ cái)

Vậy làm thể nào đề máy tính hiển thị các ký tự chữ Hán, tiếng việt hay tiếng hindi...?

Trả lời: sử dụng các Character Encoding. Và nênsửdụng chuẩn mã hóa phổ biến nhất thế giới là Unicode

---------------------

Với tiếng việt:

Input method thuận tiên nhất là TELEX

Character encoding : Unicode

-------------------

Với tiếng Nhật:

Input method: anthy hoặc mozac

Character encoding: Unicode

Câuhỏi 1:

Khi gõ 1 văn bản trên máy tínhsửdụngbàn phím QWERTY thì thuờng sẽ chỉ gõ đuợc các ký tự tiếng anh (26 chữ cái)

Các ký tự CJK (Chinese Japanese Korean) và ký tự tiếng việt sẽ không gõ đuợc

Vậy làm cách nào để gõ các ký tự mà bàn phím không có?

Trả lời: phải sử dụng các Input Method

Câu hỏi 2:

Thông thuờng máy tính chỉ hiển thị các văn bản tiếng anh (26 chữ cái)

Vậy làm thể nào đề máy tính hiển thị các ký tự chữ Hán, tiếng việt hay tiếng hindi...?

Trả lời: sử dụng các Character Encoding. Và nênsửdụng chuẩn mã hóa phổ biến nhất thế giới là Unicode

---------------------

Với tiếng việt:

Input method thuận tiên nhất là TELEX

Character encoding : Unicode

-------------------

Với tiếng Nhật:

Input method: anthy hoặc mozac

Character encoding: Unicode

COMMON VIETNAMESE INPUT METHODS

| Accents vs. Vowels Dấu với nguyên âm |

Telex

Input Method Cách gõ Telex |

VNI

Input Method Cách gõ VNI |

VIQR

Input Method Cách gõ VIQR |

| a circumflex - â | aa | a6 | a^ |

| e circumflex - ê | ee | e6 | e^ |

| o circumflex - ô | oo | o6 | o^ |

| a breve - ă | aw | a8 | a( |

| o horn - ơ | ow | o7 | o+ |

| u horn - ư | uw | u7 | u+ |

| d stroke - đ | dd | d9 | dd |

| acute - sắc | s | 1 | ' |

| grave - huyền | f | 2 | ` |

| dot below - nặng | j | 5 | . |

| hook above - hỏi | r | 3 | ? |

| tilde - ngã | x | 4 | ~ |

| remove diacritics - xóa dấu | z | 0 | - |

|

Example - Ví dụ: Vietnamese - Tiếng Việt |

Vis

duj: Tieesng Vieejt |

Vi1

du5: Tie61ng Vie65t |

Vi'

du.: Tie^'ng Vie^.t |

Most Vietnamese keyboard drivers also support some sort of smart input, which allows entry of diacritical marks at the end of the word. The driver, through some intelligent algorithm, will place the marks on the appropriate characters within the word. This automatic marking results in faster typing for users.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)